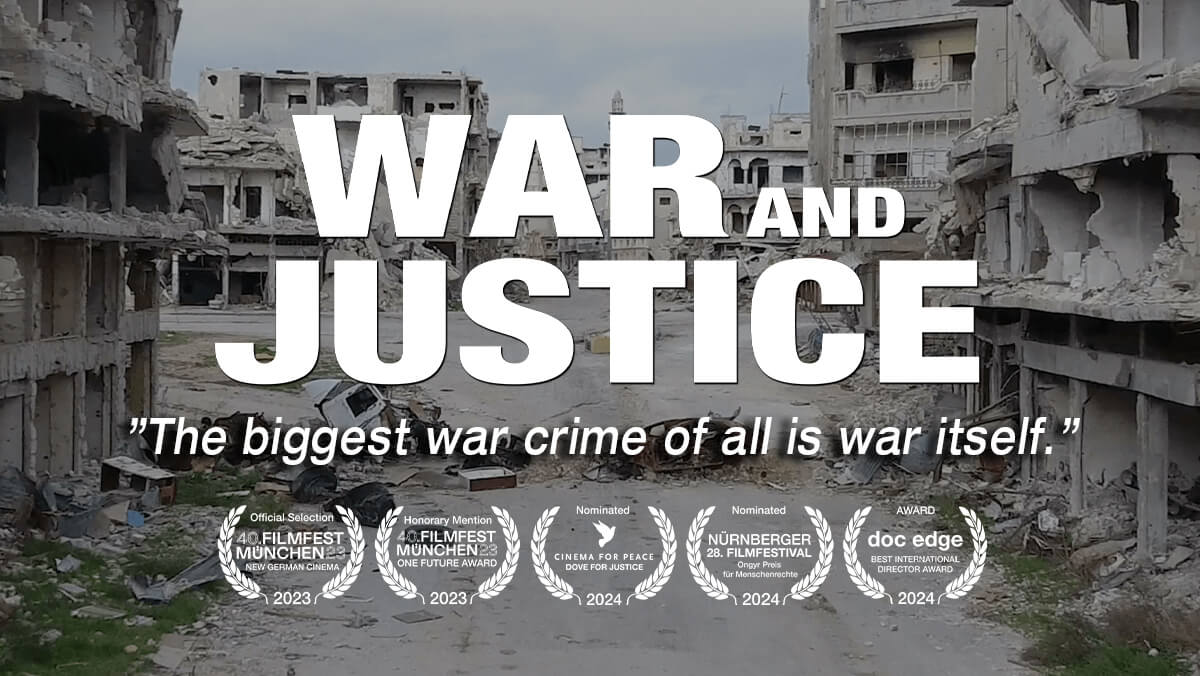

In July 1998, 120 states decided to transform the legacy of Nuremberg into a permanent institution, something that had never been done before. They pledged to prevent and punish the most serious crimes against the international community — crimes against humanity, genocide, war crimes, and the mother of all such crimes, wars of aggression. To help ensure the protection of victims, they created the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, vowing to intervene when member states fail to act. Argentine lawyer Luis Moreno Ocampo becomes the ICC’s first chief prosecutor, devoting ten long years to justice for war criminals globally. Ultimately, Ocampo hands over his post to successor Fatou Bensouda, but later returns to Europe for the first time to address the world community with a keynote speech in the same place where the prosecution of war criminals first began — Nuremburg Courtroom 600.

“Can justice replace war as a mechanism for resolving conflict?” asks Ocampo. His answer: Only with global popular support, for which films can play a critical role. Judgment at Nuremberg, the epic 1961 courtroom drama about the trials, opened the eyes of millions to the horrors of the Holocaust. Argentina 1985, released last year, showing young Ocampo as he helps prosecute atrocities by the military junta, enlightens new generations about the true difference between democracy and dictatorship. Likewise, War and Justice, following the International Criminal Court through the eyes of its chief prosecutors, sheds new light on the vicious cycle of violence that seems to be engulfing the world of the 2020s. Today, the ICC is more needed than ever before in its quarter-century history. Indeed, when Russia invaded Ukraine, 43 member states asked the ICC to intervene. Ukraine promptly accepted the court’s jurisdiction to investigate possible war crimes and crimes against humanity. But for the crime of aggression, Prosecutor Karim Kahn cannot bring Russia’s leaders to justice because of a 2017 amendment to the ICC’s statute requiring the consent of the aggressor. Nor can he prosecute wars of aggression by non-member states in the Middle East.

In the genre of a judicial thriller, the film tells how the first internationally legitimized criminal court investigates war criminals. These include cases such as the suppression of the Arab Spring in Libya, possible war crimes in the Gaza war and the recruitment of child soldiers in the Congo. The actress Angelina Jolie and UN special envoy and one of the former chief prosecutors at the Nuremberg trials, Ben Ferencz, are traveling to The Hague especially for the first trial against the Congolese militia leader Thomas Lubanga Dyilo. They want to support this young court and its acceptance by the public. Ben Ferencz, who died in April this year at the age of 103, spent his life fighting for wars of aggression to be classified as war crimes themselves. In his view, all wars lead to atrocities against the civilian population, which is unavoidable in today’s hybrid warfare.

How can mankind escape the vicious cycle of violence? What is the path forward? War and Justice provides some of the first truly viable answers.